OPAL

Opal is the product of seasonal rains that drenched dry ground in regions such as Australia’s semi-desert “outback.” The showers soaked deep into ancient underground rock, carrying dissolved silica (a compound of silicon and oxygen) downward.

During dry periods, much of the water evaporated, leaving solid deposits of silica in the cracks and between the layers of underground sedimentary rock. The silica deposits formed opal.

How Opal Forms

Opal is known for its unique display of flashing rainbow colors called play-of-color. There are two broad classes of opal: precious and common. Precious opal displays play-of-color, common opal does not.

Play-of-color occurs in precious opal because it’s made up of sub-microscopic spheres stacked in a grid-like pattern—like layers of Ping-Pong balls in a box. As the lightwaves travel between the spheres, the waves diffract, or bend. As they bend, they break up into the colors of the rainbow, called spectral colors. Play-of-color is the result.

The color you see varies with the sizes of the spheres. Spheres that are approximately 0.1 micron (one ten-millionth of a meter) in diameter produce violet. Spheres about 0.2 microns in size produce red. Sizes in between produce the remaining rainbow colors.

Although experts divide gem opals into many different categories, five of the main types are:

White or light opal: Translucent to semitranslucent, with play-of-color against a white or light gray background color, called bodycolor.

Black opal: Translucent to opaque, with play-of-color against a black or other dark background.

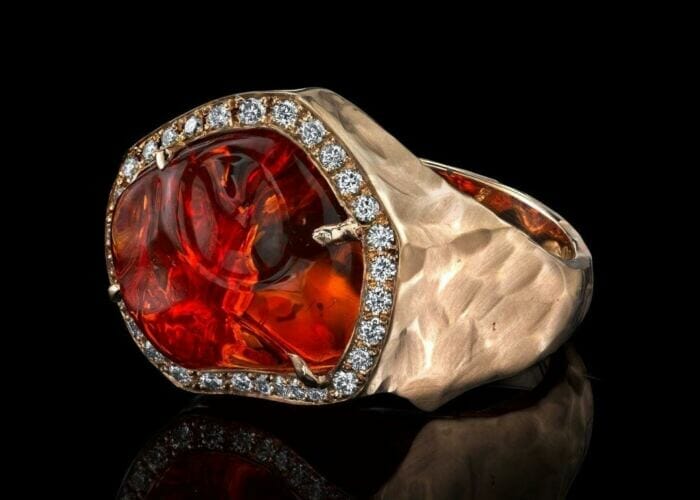

Fire opal: Transparent to translucent, with brown, yellow, orange, or red bodycolor. This material—which often doesn’t show play-of-color—is also known as “Mexican opal.”

Boulder opal: Translucent to opaque, with play-of-color against a light to dark background. Fragments of the surrounding rock, called matrix, become part of the finished gem.

Crystal or water opal: Transparent to semitransparent, with a clear background. This type shows exceptional play-of-color.

TOURMALINE

Tourmalines come in a wide variety of exciting colors. In fact, tourmaline has one of the widest color ranges of any gem species, occurring in various shades of virtually every hue.

Many tourmaline color varieties have inspired their own trade names:

Rubellite is a name for pink, red, purplish red, orangy red, or brownish red tourmaline, although some in the trade argue that the term shouldn’t apply to pink tourmaline.

Indicolite is dark violetish blue, blue, or greenish blue tourmaline.

Paraíba is an intense violetish blue, greenish blue, or blue tourmaline from the state of Paraíba, Brazil.

Chrome tourmaline is intense green. In spite of its name, it’s colored mostly by vanadium, the same element that colors many Brazilian and African emeralds.

Parti-colored tourmaline displays more than one color. One of the most common combinations is green and pink, but many others are possible.

Watermelon tourmaline is pink in the center and green around the outside. Crystals of this material are typically cut in slices to display this special arrangement.

Some tourmalines also show a cat’s-eye effect called chatoyancy. Cat’s-eye tourmalines are most often green, blue, or pink, with an eye that’s softer and more diffused than the eye in fine cat’s-eye chrysoberyl. This is because, in tourmaline, the effect is caused by numerous thin, tube-like inclusions that form naturally during the gem’s growth. The inclusions are larger than the inclusions in cat’s-eye chrysoberyl, so the chatoyancy isn’t as sharp. Like other cat’s-eyes, these stones have to be cut as cabochons to bring out the effect.

A tourmaline’s chemical composition directly influences its physical properties and is responsible for its color. Tourmalines make up a group of closely related mineral species that share the same crystal structure but have different chemical and physical properties. They share the elements silicon, aluminum, and boron, but contain a complex mixture of other elements such as sodium, lithium, calcium, magnesium, manganese, iron, chromium, vanadium, fluorine, and sometimes copper.

Gemologists use a tourmaline’s properties and chemical composition to define its species. The major tourmaline species are elbaite, liddicoatite, dravite, uvite, and schorl.

Most gem tourmalines are elbaites, which are rich in sodium, lithium, aluminum, and sometimes—but very rarely—copper. They occur in granite-containing pegmatites, which are rare igneous rocks. Pegmatites are sometimes rich in exotic elements that are important for the formation of certain gem minerals. Pegmatites might contain very large crystals up to 1 meter (about 3 feet) in length. Because of the nature of pegmatites, different gem pockets within one pegmatite body can hold tourmaline crystals of very different colors. Or one pocket can produce a variety of differently colored tourmalines. As a result, many mines produce a variety of gem colors.

Another feature of gem pegmatites is the scattered distribution of pockets within them. For miners, working a pegmatite consists mostly of excavating barren rock until the work results in the occasional and sudden reward of a rich pocket full of spectacular gem crystals.

Elbaites offer the widest range of gem-quality tourmaline colors. They can be green, blue, or yellow, pink to red, colorless, or zoned with a combination of colors.

Liddicoatite is rich in calcium, lithium, and aluminum. It also originates in granite-containing pegmatites and offers a diverse array of colors, often in complex internal zoned patterns. It’s named after the late Richard T. Liddicoat, former president of GIA and former chairman of its Board of Governors. He’s often referred to as the “Father of Modern Gemology.”

Uvite is rich in calcium, magnesium, and aluminum. Dravite is rich in sodium, magnesium, and aluminum. Both form in limestone that’s been altered by heat and pressure, resulting in marble that contains accessory minerals like tourmaline.

Some of the most important gem tourmalines are mixtures of dravite and uvite. They’re often brown, yellowish brown, reddish brown, or nearly black in color, but sometimes they contain traces of vanadium, chromium, or both. When present in the right concentrations, these impurities produce rich green hues that rival those of tsavorite garnet and, occasionally, even emerald. Dealers sell these gems as chrome tourmaline, even though they’re not always colored by chromium.

The bright yellow gems some dealers call “savannah” tourmalines are also mixtures of dravite and uvite. Their coloring element is iron.

Schorl is typically black, and rich in iron. It forms in a wide variety of rock types. It’s rarely used as a gem, although it has been featured in mourning jewelry.

(From GIA)