Humankind’s fascination with precious stones long predates the establishment of gemology. The Romans believed that diamonds were splinters of falling stars, while the ancient Greeks considered them to be the tears of the gods.

Pearls were also highly prized in ancient societies. Regarded as a currency for affection and love, the silky round bulbs were often offered to women on their wedding days to promote fertility.

Today, the value of a gem is more likely to be dictated by auction records than superstition. But while you can put a price on a precious stone, its value is determined by more than just supply and demand.

Instinctive attraction

There may be evolutionary reasons why we gravitate towards shiny objects. Research published in the Journal of Consumer Psychology suggests that gems evoke the glossy surface of a body of water. Our pursuit of them may be rooted in a simple urge to survive.

In the study, researchers blindfolded participants and asked them to touch a picture of a landscape. They were then asked to guess how much water featured in the image. Those touching glossy surfaces guessed a higher proportion of water than those given matte paper.

The study’s co-author, Dr. Vanessa Patrick, believes that the association between glossy surfaces and the images they conjure may offer evolutionary reasons for our love of shiny objects.

“We wanted to rule out the ‘pretty’ explanation,” said Patrick, who’s also a professor of marketing and director of doctoral programs at the University of Houston.

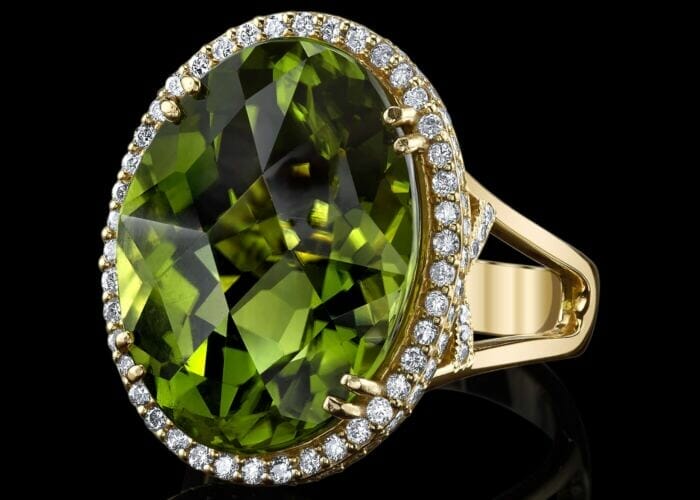

The mental associations we make with colors may also explain the value assigned to certain gems. According to author and gemologist Antoinette Matlins, blue gems traditionally represent the heavens and the seas, red symbolizes heart and passion, while green signifies rebirth and loyalty — reliable like the grass that regrows every spring.

Gem superstitions can also be gendered. Matlins says that yellow denotes secrecy on a man but generosity on a woman. White or transparent stones typically signify friendship, integrity and religious commitment for men, or purity, affability and thoughtfulness for women.

Pearls have often been used to project power, according to Inezita Gay-Eckel, a jewelry historian and professor at L’École, a Paris-based school.

“Think of Elizabeth I of England who covered herself in pearls and makeup as a shield,” Gay-Eckel said. “(She was) always walking the tightrope of not appearing unnatural and staying a woman — so that people wouldn’t think she was a monster — (while) also keeping power.

“Look at any powerful woman. From Oprah to Nancy Pelosi to Jacqueline Kennedy, when they want to project the right image, pearls are going to come out.”

Each gem has a story

Today, there are scientific ways of assessing the value of a precious stone. In addition to its rarity, a gem’s market value is often determined by its clarity, cut, color and carat — colloquially known as the “four Cs.”

But ultimately, a jewel is worth whatever bidders are willing to pay for it. Just like in the art world, contemporary culture and trends also play their part.

History can too. Worn, transported or exchanged, a gem often carries the stories of its previous owners. Some of the world’s most prized stones are valued for their pasts. The American Gem Trade Association now promotes the history of its stones by creating background cards to accompany those it sells, said Matlins.

“The (idea of) information (cards is) only a couple of years old, but retailers and customers love it,” she said. “Almost all colored gemstones carry a story.”

As cultural artifacts, gems can reflect the technology and the values of the civilizations that celebrated them, from carved Moghul emeralds to Chinese burial suits made from jade.

“Each one says something about the skill of the artisans, and the values of the societies that produced them,” said Duncan Pay, editor-in-chief of the Gemological Institute of America’s quarterly peer-reviewed journal, Gems & Gemology. “Natural gems really are tiny sparks wrought from the depths of the Earth. They’re (also) invested with the spirit and energy of the men and women who mined them.”

Defining value

Of course, value isn’t always monetary. At L’École jewelry school, which begins a series of classes in Hong Kong this month, students are taught to address a gem’s worth through a broad range of factors, according to Gay-Eckel.

“If people want to know what makes jewelry valuable, we give them knowledge about everything that’s around it,” she said. “What goes into making it, how to enjoy the stones and how to obtain the knowledge with a sense of discovery and satisfaction. Do you love it? Is it something your mother gave you?”

For scientists, gemstones’ value is drawn from the precious insights they can offer into plate tectonics — and the mountains, oceans and environments of the past.

“The gem deposits of eastern Africa trace the outline of ancient mountains that once connected Sri Lanka and Madagascar over 500 million years ago,” said Pay.

“And the oldest emeralds formed just under three billion years ago, which rivals the age of some diamonds.”

Perhaps jewels’ true worth lies in these timeless qualities. Having survived for millennia, gemstones have long been considered reliable investments, as they continue to hold their value through the generations.

“Of all of the ways to adorn yourself, what has nature created that has lasting beauty like a rock?” Matlins said. “As soon as you cut a flower, it wilts. A sunset is beautiful but you can’t capture or wear it. There is something so special and everlasting about nature’s creation of minerals and rocks.”

From Marissa Miller, CNN